Michael Rushton does it again, this time calling BS on arts districts. open.substack.com/pub/micha…

A Personal Project

I began a new project a few days ago. In many ways, it is the opposite of the Learn in Public orientation. In fact, it is intentionally Learn in Private.

I have been writing (and learning, and sharing) in public for 20 years, and it has been great. I’ve learned a lot, and I flatter myself in thinking that my writing made at least a little difference to those who were trying to re-imagine theater. But the overlap between the Venn Diagram of Learning in Public and Teaching in a Classroom is almost total, at least for me, and that has become somewhat of a crutch. To teach involves an outward orientation: what does the student/reader need to know in order to understand this step? What does the student need to hear at this moment? Even though I retired in 2020, I have found myself continuing in the habit of asking these questions as I’ve written books and blog posts.

In addition, when I started in blogging in 2005, the scene was a lot like social media today–very contentious. Either you were reacting to someone else, or you were the one being reacted to. And soon I found I was becoming like Benvolio as described by Mercution in Romeo and Juliet:

Thou—why, thou wilt quarrel with a man that hath a hair more or a hair less in his beard than thou hast. Thou wilt quarrel with a man for cracking nuts, having no other reason but because thou hast hazel eyes. What eye but such an eye would spy out such a quarrel? Thy head is as full of quarrels as an egg is full of meat, and yet thy head hath been beaten as addle as an egg for quarreling. Thou hast quarreled with a man for coughing in the street because he hath wakened thy dog that hath lain asleep in the sun. Didst thou not fall out with a tailor for wearing his new doublet before Easter? With another, for tying his new shoes with old ribbon?

In my defense, there were a lot of quarrels that needed to be had. But eventually all this becomes a habit rather than a choice, and (to quote Shakespeare again) you become “damned, like an ill-roasted egg, all on one side.”

So it’s time for me to learn how to have an inward orientation. To ask not what does the student need, what argument needs to be countered, what information is missing from the world, but rather what do I need. And that’s a question I have avoided.

At 66, I’ve done a lot of reading and thinking over the years, about a variety of topics. My specialty is theater, obviously, specifically theater history and criticism, but I have done an enormous amount of reading in literary criticism, rural issues, theology, philosophy, political philosophy, education, entrepreneurship, business models, myth and anthropology, psychology, social media, economics, anarchism, and many, many more. Lately, I’ve been having an interesting experience of encountering, in something I’m reading or a podcast I’m listening to, a person or movement or idea that provides the link between two people/movements/ideas that I’ve previously encountered and appreciated, but seemed to be floating out there in mental space without a context or tradition. So I want to spend some time taking a step or two back in order to try to recognize the pattern in my own carpet – i.e., to examine my intellectual journey and figure out what I believe. And in order to do that, I have to learn how to look inward.

I hasten to say that this is not some sort of an announcement that I am not going to continue to write publicly, about theater or anything else. I fully anticipate that I will continue doing so, perhaps even more frequently, with the only possible change being a broader pallette of thoughts. But I will also have this private project that I likely won’t share with anyone except maybe family at some point.

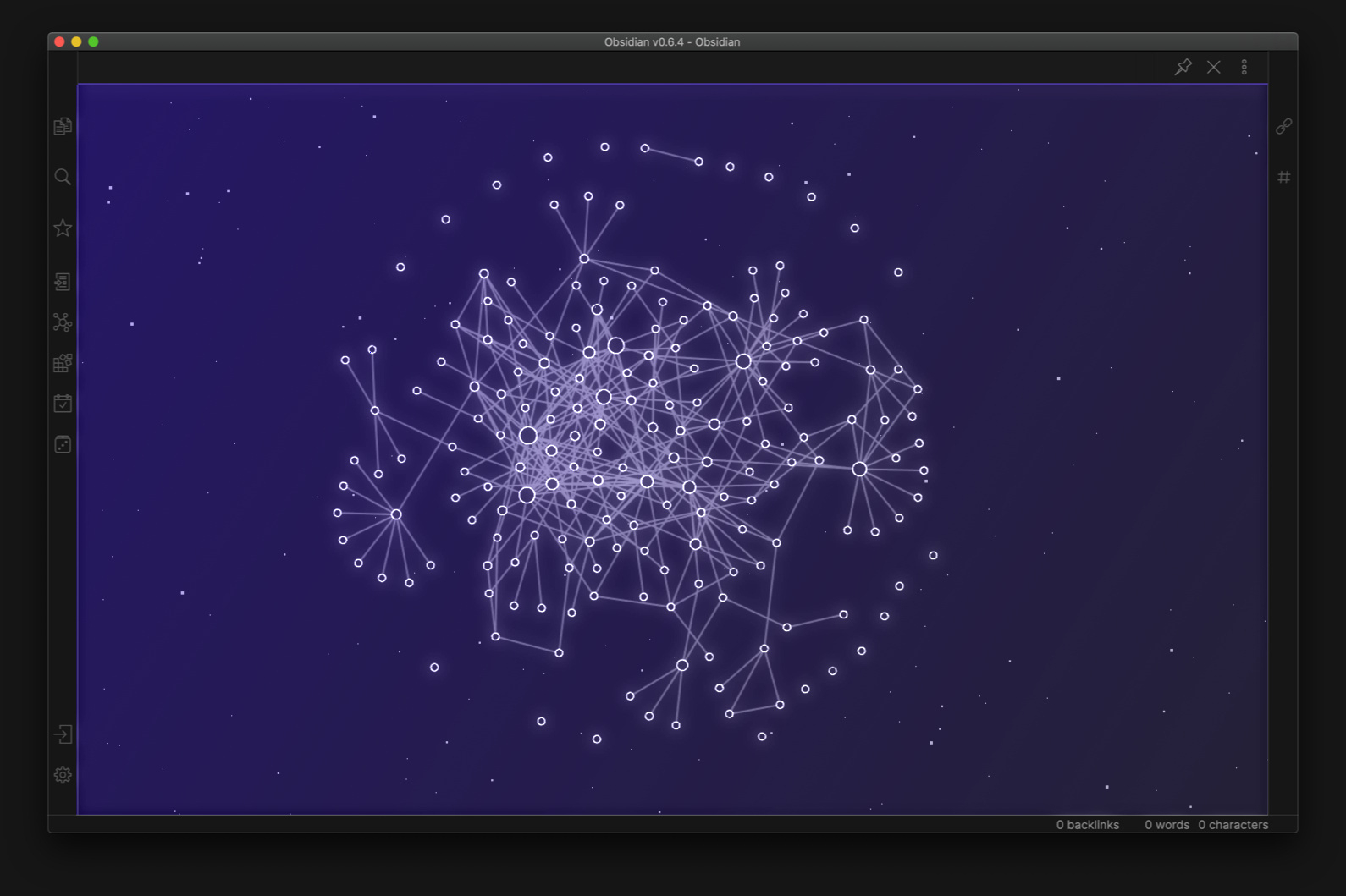

Maybe you’re curious what this might look like. I can tell you it won’t be linear–I’m not writing an autobiography. It will be more like the independent web of the early days: a bunch of pages on different topics hyperlinked together. I’ll be using Obsidian, which is what Obsidian is best at. I suspect the result might look like an Obsidan graph view:

But for readers, it will be like a choose-your-own-adventure book of pages with text and links. Nothing fancy.

My hope is that this process, which I expect will go on for quite a while (if not the rest of my life) will lead to greater self-understanding, as well as to future sources of inspiration–“breaking bread with the dead” (and the living!), as @ayjay would say. And I also hope the process will lead to intellectual or emotional explosions in my mind, like a star exploding in space, producing a massive burst of light, heat, and high-energy particles along with a shockwave of expanding intellectual material. Enlightenment! Or a major headache. One or the other.

On the other hand, it might just be a private version of digital gardening where I can putter to keep my mind active. Either way, it is a net plus.

If you have any examples or suggestions, feel free to share. I see something like Maria Popova’s The Marginalian, or Christopher Alexander’s A Pattern Language as inspiration. I know there are many more precursors, and that this is nothing new or original. But I think it will make me happy, which I’m trying to learn is sometimes enough.

“The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world, full stop. Unless we can inhabit that distinction, we will end up defending the world as we have known it at all costs, no matter how monstrous those costs turn out to be.”

At Work in the Ruins by Dougald Hine

Gradually, Then Suddenly: The Birth of Show BUSINESS (Part 2): The Resistance

The Resistance

The attempt by the six members of the Theatrical Syndicate to create a monopoly of the road was, of course resisted. But for the rank-and-file actors, the war was over in the 1870s when the combination companies killed the resident stock companies and actors were forced to move to New York in order to pursue their careers. They had no ability to resist this change--Actors Equity didn't appear until 1917.

No, this is a battle between stars (I.e., the actor-managers who headed their own combination companies) and real estate tycoons of the Theatrical Syndicate. These were the Big Boys duking it out.

As you probably remember from my [last post on this topic](https://scottwalters.micro.blog/2025/02/27/gradually-then-suddenly-the-birth.html), in 1896 the members of the Syndicate pooled first-class theaters they owned, and there were a bunch: "according to Monroe Lippman, writing in The Quarterly Journal of Speech, the members of the Syndicate 'controlled nearly all the first-class theatres in the key cities throughout the country, in addition to enjoying exclusive booking control of more than five hundred first-class houses on all the best theatrical routes from the Atlantic to the Pacific and from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico.'” But the Syndicate wasn't done--oh no, not by a long shot. "The aim of monopoly is to eliminate competition," writes Douglas McDermott. And there was still some competition to deal with.

So once they had signed their contract formalizing their business arrangement (which they denied existed for several years until a court case--'a syndicate? No! We're just friends!'-- forced it to be revealed), "the theatrical trust began a campaign to secure control of the remainder of the first-class theatres in America, either through leasehold or by promises to theatre managers of the best attractions available. Their targets included theatres in Minneapolis, St. Louis, Cleveland, Detroit, and other major cities not yet under Syndicate control, theatres in towns that controlled the approaches to the big cities, and one-night-stand houses in between."

Within just a couple years, the Syndicate had locked down theaters across the country, and they then informed the actor-managers that they had two choices: either sign with the Syndicate or go elsewhere--there being, of course, nowhere else to go. Francis Wilson, one of the actor-managers who, along with Minnie Maddern Fiske, wrote "The contention of the Syndicate was that it must control the 'bookings' of theatrical companies throughout the country in order to avoid the ruinous opposition that happened from two prominent companies appearing in the same city or town at the same time; also that it could not run its theaters and pay the percentages demanded by some unattractive "stars" whom it did not wish to “book” at a loss. There was reason in the first plea, none in the latter."

To the local theater manager, the Syndicate would promise a steady stream of the country's best productions, making it possible to book "for an entire season without an expensive annual business trip to New York, and an end to empty theaters caused by performers' failure to appear without notice. To the actor-managers and their company who still booked their own tours, "they promised efficient, economical routes composed of first-class theatres in any region of the country or even coast to coast. In short, the Syndicate offered everyone involved in the Road greater prosperity and security than they could attain on their own. For their services, the Klaw and Erlanger Exchange claimed a fee of 5 percent of a theatre’s gross receipts." In other words, the Syndicate was doing everybody a big, fat favor. And so cheap, too!

At first, this pitch worked. According to John Frick, "As Syndicate members had hoped, theatre managers and booking agents flocked to the Klaw and Erlanger offices to sign contracts. In their first two years of operation, using little more than their ingenuity, persuasion, and their influence in the theatre, the Syndicate more than doubled the number of theatres it controlled, secured the contracts of stars with the stature of E. H. Sothern, Ethel Barrymore, Mrs. Leslie Carter, Blanche Bates, and Olga Nether-sole, and developed into a monopoly in actuality, not just in intention. With a strong nucleus of theatres and attractions, by 1898 the Syndicate was in a position to exercise its power overtly and to dictate terms to both theatres and performers."

But then things changed. Frick:

With its power and holdings consolidated, the Syndicate began to behave like any other monopoly - it threatened to withhold what it controlled from those who declined its terms. Theatre managers who refused to ally themselves with the Syndicate were unable to book high-quality talent or were forced to watch helplessly as the Syndicate built or leased a theatre nearby; meanwhile, recalcitrant performers might be routed from Cincinnati to Washington to Buffalo to Richmond with no intervening bookings, denied a route altogether, or, as in the case of Henrietta Crosman’s 1901 tour of Mistress Nell, led to discover that a rival production (Ada Rehan in _Sweet Nell of Old Drury_) had been booked for the same route a week earlier. Thus, by controlling both sides of the booking equation - theatres and attractions - and threatening to withhold one or the other, Klaw, Erlanger, and company were able to force all but the most stalwart to capitulate to their demands."Some of the actor-managers had had enough. Frick:

In 1898, following a series of editorials criticizing the Syndicate in the New York Dramatic Mirror by its editor Harrison Grey Fiske [who was married to a member of the resistance, Minnie Maddern Fiske], the [Syndicate] faced its first public opposition in the form of an actors’ uprising, the first of many it would face. Convinced that their artistic freedom was being curtailed by the Syndicate, the actors - Richard Mansfield, Francis Wilson, James O’Neill [yes, Eugene's father], William H. Crane, Fanny Davenport, Joseph Jefferson, and Mrs. Fiske - vowed to maintain their independence and to aggressively defy Klaw and Erlanger’s dictates.They made impassioned speeches from the stage prior to performances to make sure the spectators understood what was happening, they published editorials in the nations' newspapers. A few examples:

- **Joseph Jefferson**: --"When the Trust was formed, I gave my opinion as against it, considering it inimical to the theatrical profession. I think so still." [OK, that one is kind of lame.]

- **Richard Mansfield**: --"Art must be free. I consider the existence of the Trust or Syndicate a standing menace to art. Its existence is, in my opinion, an outrage and unbearable." [Way better.]

- **Mrs. Fiske**: --"The incompetent men who have seized upon the affairs of the stage in this country have all but killed art, worthy ambition, and decency." [Boo-yah]

- **Francis Wilson**: --"Dramatic art, in America, is in great danger. A number of speculators have it by the throat, and are gradually but surely squeezing it to death." [Ka-Boom!]

I don’t want to trivialize their effort–they weren’t wrong. It’s just that artists have been making the same arguments ever since, except in the face of new opponents, like, say, legislators skeptical of providing government funding for the arts. Did writers and other artists do any better?

- James A. Herne (playwright): –“The underlying principle of a Theatrical Trust is to subjugate the playwright and the actor. Its effect will be to degrade the art of acting, to lower the standard of the drama, and to nullify the influences of the theatre.”

- Augustin Daly (drama critic, theatre manager, playwright, and adapter, the first recognized stage director in America): –“I do not believe that the best interests of dramatic art nor the highest aims of the theatre will be served if the spirit of competition is chilled, crippled, or destroyed; and the first aim of all such combinations or syndicates must be to absorb opposition and to kill off rivals or rivalry.”

- Henry Irving (British actor-manager): “When I was in America, lately, a deputation of actors assured me that the Syndicate System is the curse of the American stage. Actor-managers, at all events, have made sacrifices for their calling, and protected its interests, and it will be an evil day for those interests when they are left to the mercy of speculation.” And all they had to do to take advantage of this generous offer was to let the Syndicate pretty much control their careers.

- William Dean Howells (bestselling novelist): –“Not merely one industry, but civilization, itself, is concerned, for the morals and education of the public are directly influenced by the stage. Everyone who takes a pride in the art of his country must regret a monopoly of the theatre, for that means ‘business’ and not art.”

- Thomas Bailey Aldrich (editor of the Atlantic Monthly): –“The inevitable result of a Theatre Trust would be deterioration in the art of acting and discouragement of dramatic literature. Certainly that is not a consummation devoutly to be wished.”

It’s not that they’re wrong, it’s that nobody outside the theater gives a shit about these arguments.

Nevertheless, Frick says, “for the remainder of the Syndicate’s existence, a coterie of some of America’s most respected critics and scholars, led by Walter Prichard Eaton and including John Ranken Towse, Sheldon Cheney, William Winter, and Norman Hapgood, indicted it, not just for the conventional industrial crimes (dictatorial management style, pressure tactics, and unfair labor practices) but for debasing the art of the theatre as well.” They charged:

that the Syndicate destroyed the quality of American acting by keeping players in long runs, thereby preventing them from assuming the variety of roles necessary to develop artistic versatility, and by undermining the stock company that had traditionally served as the training ground for performers. Second, the critics claimed that the Syndicate discouraged native drama, favoring instead the foreign scripts preferred by Frohman. And third, they asserted that in order to appeal to the largest audience possible for strictly commercial reasons, it discouraged “serious” drama and mounted popular “fluff” like _The Soul Kiss_, _Miss Innocence_, _The Queen of the Moulin Rouge_, and _The Girl with the Whooping Cough_.Does any of this sound familiar, Dear Reader? Has anything changed in the 125 years since these arguments were being made? One glance at the plays available on Broadway in recent years leaves one longing for a revival of _The Girl with the Whooping Cough_. Or perhaps to develop the whooping cough oneself, preferably during intermission, so you can just go home. Maybe that's just me.

At any rate, when all was said and done, the Theatrical Syndicate emerged victorious. One by one, each actor-manager was starved into submission. The only successful challenge, ironically, came from the Shubert Brothers (Sam, Lee, and Jacob), producers who joined up with a few of the rebellious actor-managers to oppose the Syndicate. But they did so not because they objected to the effect of the Syndicate's monopoly, but rather because they wanted a piece of the action. "Emulating the Syndicate’s methods during the first decade of the century," Frick writes, "the Shuberts continued to acquire theatres and entire circuits nationwide and, exploiting the rapidly growing discontent among managers and performers with the constraints imposed by Klaw and Erlanger, they offered to assist anyone who resisted the Syndicate. As a show of good faith, the brothers guaranteed an “open door” policy in the booking of Shubert theatres."

By 1905, the Shubert's "underdog status attracted defectors from the Syndicate in ever-increasing numbers. By 1910, one decade after the Shuberts’ arrival in New York, the Syndicate had been successfully challenged; during the subsequent decade, it was fully eclipsed by the Shubert organization, which, through continued growth and acquisitions, became a monopoly that was virtually indistinguishable from its predecessor in intent, methods, and scope." But there was an unintended consequence, according to Frick:

"the period of fiercest competition between the two conglomerates (1909-13) was also the period during which the Road began its legendary decline, with the number of traveling combinations shrinking from 289 in 1909 to 178 four years later. As [Rudolph] Bernheim summarizes the situation, intensified competition brought an oversupply of theatres, as the Shuberts built or converted spaces in Syndicate towns to match their opponents house for house. The theatre glut, in turn, created a shortage of quality attractions. With vast chains of theatres to fill, panicky producers and bookers from both sides of the theatre war responded by cloning additional duplicate companies and billing them as “Straight from a Year on Broadway” with the hope that patrons in the hinterlands would not notice the ever-diminishing production values. However, spectators, perhaps remembering the great touring plays and players of earlier decades and refusing to be gulled by inferior productions despite advertisers’ puffery, stopped patronizing the legitimate theatre, thus adding the final link in the causal chain that ultimately led to the decline of the Road."Ultimately, however, the damage had been done.

- theater casting was centralized in New York, and actors were forced to move there in order to make a living; - as the road declined, the Syndicate and the Shuberts sold off most of their small-town theaters, relying solely on tours to the largest cities; - businessmen managing real estate, now called producers, became the most powerful people in the theater; - as predicted, profit became more important than the quality of plays - and the number of productions began a slide to the pathetic level of today's theater.

So Why Should We Care?

“The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently." -- David Graeber

"The exercise of imagination is dangerous to those who profit from the way things are because it has the power to show that the ways things are is not permanent, not universal, not necessary.” ~Ursula K. Le GuinFor some reason, theater people have been taught that the way things are is the way they always have been, and if they were different before it's because "things were different then" and this system is the best of all possible worlds. It's a meritocracy! And if you can't "make it," well, that must mean that you just don't have enough talent or enough commitment to make the cut.

This is errant nonsense. It is what the owners want artists to believe, because they benefit from the current system.

Have there been different systems in the past? Yes. We've already described the resident stock company system that preceded the arrival of the combination company. But there have been others since the Syndicate took over.

For instance, it didn't take long after the Syndicate for movement to revolt against it. It was called the Art Theater Movement, and it gave us many important theaters and artists. For instance, the Provincetown Players were part of the Art Theatre Movement, and without them and without Jig Cook and Susan Glaspell, we would not have Eugene O'Neill. The Neighborhood Playhouse was part of the same movement, and the Theatre Guild. Sheldon Cheney, whose book _The Art Theater_ is an invaluable and inspiring account of the major theaters and artists of that time, defined the art theater as one "dedicated to creative staging of important plays...From the audience's viewpoint," he wrote, "an art theater implies a _playhouse permanently established_, where a spectator can go always with the assurance of seeing _fine plays of the past or present_ beautifully acted and adequately staged. From the viewpoint of the artist-producer, the art theater is:

a place where the arts of the theater are creatively practiced, free alike from the will of the businessman_, from the demands of movie-minded audiences, and from the fetters of superstitious traditionalism; he probably entertains, moreover, a vision of the several contributive arts of the playwright, the actor and the designer brought together in a union or synthesis, and in the final result invariably stamped with the style or the brilliance or the quality of his own mind or imagination—_this viewpoint implying an aesthetic policy and a lasting association of creative workers under artist-leadership_." [emphasis added]Why yes, that _does_ sound like the regional theater movement of the 1950s and 1960s, which was another movement that pushed back against the crass commercialism of Broadway and strove to create permanently established theaters with a long-term commitment to artists performing plays from the past and present free from the will of the businessman.

In between the Art Theater and the Regional Theater, there were other notable and successful attempts to focus on art as art rather than commerce.

But rather than outline them all, I am going to suggest several books that will inspire you to think differently.

- _The Art Theater_ by Sheldon Cheney. I defy anyone to read this book without feeling inspired to strike out in a new direction. You can read it free at the [OpenLibrary.org](https://openlibrary.org/works/OL1150120W/The_art_theatre).

- [_At 33_ by Eva Le Gallienne](https://search.worldcat.org/title/At-33/oclc/1153280966). For reasons I cannot comprehend, Le Gallienne is rarely mentioned anymore, yet she had one of the most daring and successful theaters of the late 1920s and early 1930s: the Civic Repertory Theater. She was a highly successful Broadway actress who walked away from her career because she felt that the long run was killing the creativity and development of actors, and the plays were empty. "Too much cake," she declared, "not enough bread." She felt strongly that high-quality plays should be affordable and accessible to all people who wanted to see them--plays by Ibsen, Chekhov, Shakespeare, Dumas, and contemporary plays as well--and she ran in rotating repertory, eventually having 37 different productions available to perform.

- [ _Theatre in the Round_ by Margo Jones](https://search.worldcat.org/title/77659). The regional theater movement was founded by women, and Margo Jones was the dynamo. This book, like the previous two, will inspire you and restore your sense of purpose. Read this first, and then read [Zelda Fichandler's _The Long Revolution_](https://search.worldcat.org/title/1419873213) (edited by Todd London), co-founder of the Arena Stage and the regional theater movement. These two books might just get you to realize why an arena theater is particularly valuable for artistic independence.

- [_Arena: The History of the Federal Theatre Project_ by Hallie Flanagan](https://a.co/d/hd1NkdI). Do you see a pattern here? Yes, resistance to the theater of commerce was often led by driven, idealistic women who got things done. Flanagan's book describes the values that informed yet another influential theater movement outside of Broadway, while also showing us why relying on the government for, well, just about anything is a risky business indeed. The mind boggles at what might have been had not the Dies Committee killed the Federal Theatre Project. You could also read Todd London's anthology, [_An Ideal Theater: Founding Visions for a New American Art_](https://a.co/d/2axrcuM) to get started. I have used this book in several of my classes when I was teaching, and it was always an eye-opener.

But the reality is that, whether you want it to or not, the current theater system is starting to collapse. There are 41 theaters on Broadway, 33 or which are owned by three organization: the Shubert Organization, the Nederlander Organization, and ATG Entertainment, all of which also have producing arms. So the real estate men still are making the artistic decisions for America. The number of new productions on Broadway has flat-lined at 38-40 new productions per year, only 20% of which make any money. Well, I mean, the investors may not make money, but those three organizations make money as long as there are shows in their buildings.

Meanwhile, the nonprofit stage has been on the ropes since the pandemic, a fact that I've written about a lot. Many of those who are still standing are staging productions of old standards of the commercial stage.

The brilliant essayist Rebecca Solnit wrote in her book _Hope in the Dark_, "Resistance is first of all a matter of principle and a way to live, to make yourself one small republic of unconquered spirit." That's the first step toward escaping this collapse: sharpen your principles and develop an unconquered spirit. And one way that can help you with this is to find others in the past who did something similar. There are more than you think--I have only been writing about America's leaders, and only theater people; there are so many others across the world, throughout theater history, and in other art forms who can provide inspiration, strength, and models to draw upon for the future. It is going to take a combination of creativity and historical awareness to start something new and keep it going.

This series about might allow you to say that the Emperor has no clothes, while also recognizing that there are closets filled with beautiful styles placed there by past artists for you to try on. You don't have to keep rolling an artistic boulder up a > commercial, centralized, and dysfunction hill. Develop your own vision./end

You know what I think is weird? That people will condemn you for not keeping up with the news while they think nothing about ignoring philosophy, literature, theology, cultural criticism, history. You will be at the mercy of spinmeisters if you lack a worldview that structures the news.

Thoughts on Style While Feeling Crummy (Embracing My Inner Paglia)

I wrote this in 2009. I still basically feel the same way.]I am at home with a cold. Forced by my body to stop the quotidian forward motion from prep to class to prep to class and then to grading, I find myself propelled instead toward reflection, bleary and slightly feverish though I am.

The catalyst for this introspection, which will likely take an outward turn, is Camille Paglia. On Saturday, in an almost accidental way, I picked up her 1992 book Sex, Art, and American Culture at the local branch library. As I leafed through its pages, it seemed as if the book would spontaneously combust as a result of the attempt to contain Paglia’s intense personality. I happened to open to her almost ritualistic dismemberment of David Halperin and Michel Foucault, and I found myself rubber-necking as if I were passing the scene of a grisly highway accident. I checked the book out, along with a few others, and took it home where the next day my feverish brain fell completely under its spell.

There is a lot Paglia says that I don’t agree with – her aesthetic preferences and mine differ significantly at times, and I suspect that a conversation with her might be more monologue than dialogue – but I was enthralled by her slash-and-burn prose, and her iconoclastic a-plague-on-both-your-houses independence. I was reminded of Emerson’s injuction to “Speak what you think to-day in words as hard as cannon balls, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict everything you said to-day. " Paglia’s style unleashes an entire arsenal.

I like that in a writer. I like the fact that Paglia, who got her graduate degree from Yale’s Harold Bloom and whose learning is prodigious, writes that with “most academics, I feel bored and restless. I have to speak very slowly and hold back my energy level.” It is her energy level, and her courage, that speaks loudest. I suspect that is why I enjoyed Ayn Rand’s Romantic Manifesto[I shudder to admit this], although I found her aesthetic judgment horrible.. Her writing style was clear Appollonian fire, like the blue flame of a metal cutter. I learned something from her. I like John Taylor Gatto, the anti-education teacher-of-the-year winner whose dissection of the banality of compulsory education is fiery and principled. I like business writer Tom Peters, who wrote in the introduction to his incendiary book Re-Imagine, “I don’t expect you’ll agree with everything I say here. But I hope that when you disagree, you will disagree angrily. That you will be so pissed off that you will…Do Something. DOING SOMETHING. That’s the essential idea, isn’t it?” Yes, it is. In 1956, Jimmy Porter sounded the alarum in Look Back in Anger when he demanded “a little human enthusiasm,” and condemned the fact that ““Nobody thinks, nobody cares. No beliefs, no convictions and no enthusiasm.” Fifty years later, the torpor continues.

Our world, our educational system, and our arts have become Fogelberged. We have traded passion, intensity, and integrity for mushy sensitivity and adolescent pique. We condemn the identification of bullshit as “intolerance” and an insistence on intellectual standards as “insensitive.” And it is the worst in academia and the arts, where we are so fearful that we will damage students' and faculty’s self-esteem that we applaud any piece of garbage that either produce. Graduates take that expectation of easy acclaim out into the world, where they get all in a huff when some critic says anything even mildly critical of them or one of their chums. Members of the theatrosphere justify their unwillingness to write anything less than adulatory on the basis of self-preservation, as if personal integrity was unimportant and honesty the equivalent of a raodside bomb.

After ten years of trying to toe that line, I’ve had enough. Theatre is hard, and there is a lot to learn. Failure will be constant, and should not be seen as anything but failure. You learn more from failure than success, but only if you look deeply at the failure and mine it for its treasure. There are thousands of years of theatre history. and theory, and criticism, and they need to be learned before young artists have the right to be taken seriously. And even then, there is more anthropology and psychology and philosophy and comparative religion to be understood before they have anything to say that will be of interest to anyone older than fifteen.

Our theatre is shallow, and it is because young artists emerge from their undergraduate and graduate experiences uneducated, unread, and unchallenged. If they read more than a couple dozen plays over the course of four years – and I mean read the plays, not the on-line Spark Notes – it is a rarity. Theory? Forget it. The understanding of Aristotle, Brecht, Schiller, and dozens of others is shallow or non-existent. Theatre students spend their time focused on “doing plays,” and none of their time trying to figure out why they ought to be done in the first place, and what they have to say to the world today. They sit bored through any class that isn’t a “how to” subject, and the faculty, most of who themselves are the product of how-to education, condone their apathy as an artistic temperament. Bullshit. Boredom is the sign of a shallow approach to experience. I am reminded of the aforementioned John Taylor Gatto, who wrote about his grandfather: “One afternoon when I was seven I complained to him of boredom, and he batted me hard on the head. He told me that I was never to use that term in his presence again, that if I was bored it was my fault and no one else’s. The obligation to amuse and instruct myself was entirely my own, and people who didn’t know that were childish people, to be avoided if possible. Certainty not to be trusted.” I feel the same way. Most young artists aren’t to be trusted with the power that is embedded within the theatre. Neither can their faculty. And neither can their artistic leaders.

If we wanted proof of the mindlessness permeating the contemporary American theatre, we need look no further than the latest edition of American Theatre. In the midst of a massive social and economic crisis, one that not only will affect the arts but also one in which the arts could conceivably play an important role through the telling of a new story about who we are, Teresa Eyring, the titular head of arguably the most important organization on today’s theatre scene, took to the bully pulpit, Marilyn Monroe-like, to burble a Happy Birthday to Facebook. Could we get a grown-up back in charge, please?

Closer to home, theatre education is a mess. The sacred cow of most theatre departments is production. Everything is fine as long as production after production is cranked out year after year with no purpose beyond simply “doing plays.” Most theatre departments are little more than play clubs, like chess club only with more resources and better cleavage. Production is seen as an end in itself, filled with intrinsic good that comes from the mere fact of learning lines and saying them in front of a set under the bored eyes of general education students required to be there for a “cultural event.” Across campus, other departments actually contribute new knowledge to their field; not theatre. Somehow, we have decided that a production in and of itself qualifies as “creative activity,” and should be taken seriously as “scholarship.” What a con job. Theatre departments ought to be the Research and Development arm of the theatre, where a stable budget allows true experiment, complete with hypothesis, experiment, and analysis all reported for the benefit of the field.

Over the years, I have tried to be polite about this, taking a “bless their heart, they can’t help it” attitude toward the mediocrity that permeates my chosen profession. But enough is enough. I am embracing my inner Paglia, polishing up my Rand, flexing my Gatto, and grabbing my Peters (har har). Back on January 30th, perhaps in anticipation of today’s post, I changed my Facebook status (no doubt a high artistic expression in the eyes of Teresa Eyring) to “Scott is determined not to dumb down what he does.” A friend of mine from grad school days wrote, “What the hell is going on? You probably don’t want me to write the admin at UNC to tell them to back off academic freedom, but I’d like to hear details.” The enemy is us, not the asdmin. It is about lack of rigor, lack of curiosity, lack of engagement. And it is about how four decades of careerist nonsense passing as education has bled our theatre scene white.

Theatre may not be dead, but it sure is dumb. Tony Kushner, about the only contemporary theatre person left with a brain, said it all quite powerfully in 1998 when he published “A Modest Proposal” in American Theatre. The lack of response from the field was deafening. No doubt, Kushner just ought to change his Facebook status.

Gradually, Then Suddenly: The Birth of Show BUSINESS (Part 1)

In Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, a character is asked how he went bankrupt. “Two ways,” he responds. “Gradually, and then suddenly.” He could have been talking about the changes to the American theater in the last quarter of the 19th century. In my February 23 post I described “The Rise of the Combination Company and the Death of the Resident Stock Company.” Today, I want to describe the capture of the American theater by businessmen.

Gradually

You probably remember that the combination company was a single, self-contained production that was cast, rehearsed, and first performed in New York City for a long run, and then toured the country intact via train. In 1870, these companies could be counted on one hand, but by the end of that decade the number had exploded to more than 250. As a result, resident stock companies collapsed, and the theater managers were left to fill their houses with full-scale productions as best they could.

Initially, the booking of combination companies was done very informally: the theater manager would send his assistant to New York City to meet with representatives of the various stars or shows to make arrangements. There were no contracts, just understandings and handshakes. Not surprisingly, there were problems with this system. Theater historian Jack Poggi notes that the actor-manager of a combination company was faced with a difficult problem:

Railroad fares were a major expense, and he had to avoid backtracking and long jumps between engagements. He also had to keep in mind the seating capacity and price scale of the theaters where he was booked (his profits were based on a percentage of the gross receipts), the relative prosperity of the areas he planned to visit, and the type of production that would precede him. In such a complex and changeable situation, both [the combination producer and the local theater manager] tended to look upon their agreements as highly tentative. If an opportunity arose to change a route in such a way as to increase his profits, the producer was quite likely to cancel a contract— perhaps without notifying the other party.

If this happened, it obviously was a disaster for the local theater manager. Poggi goes on:

The local manager might protect himself from such outrages by booking two productions for the same evening, confident that only one of them was likely to show up or that, if both did, he could put one off or (as a last extreme) resort to a double bill. But double bills cut into the profits of both the production and the house, and the local manager was especially disturbed by them if he had nothing scheduled for the following night.

Poggi concludes, laconically, “There was an obvious need for a more centralized system of booking.” Be careful what you wish for.

The first step to solving this problem was the empowerment of booking agents who, for a fee, would negotiate with the actor-manager and the local theater managers to plan a route throughout an area of the country. Booking agents were sort of travel agents for the theater.

But Dear Reader, don’t heave a sigh of relief at what seems a simple solution to this coordination problem without recognizing the ramifications: there now was a middleman standing between local theaters and theater artists, whose power was acquired because, well, it was just easier to hire someone else to handle all those pesky details. After all, the actor-manager had to handle a lot on his plate as far as the production was, and the local theater managers had to handle all the details of advertising, public relations, and building management.

But it was by controlling bookings that the members of what became known as the Theatrical Syndicate monopolized the American theater and brought the actor-managers and the theater owners to their knees.

The Power of Real Estate

Once the production of plays shifted to New York and local theaters no longer were homes to resident stock companies, owning and managing a theater no longer required knowledge of how theater was made. It was a real estate deal, plain and simple, and entrepreneurs moved in to with the sole intent of making a buck. These managers had little interest in the plays that filled their theaters beyond whether they would draw an audience. A play was merely the means for making a profit. In addition, theater owners no longer needed to live in their localities, they just needed to hire someone to do the caretaking.

By the 1890s, six wealthy men owned a large percentage of theaters across the country. The firm of A. L. Erlanger and Marc Klaw owned or leased many theaters in important cities and had exclusive booking rights to about two hundred more, mostly in small towns in the Southeast. Charles Frohman, though more famous as a producer, and his partner Al Hayman, owned several theaters and, more importantly, ran a booking agency that controlled about three hundred theaters in the West. In addition, Samuel F. Nixon and J. F. Zimmerman owned the four most important theaters in Philadelphia, as well many first-class theaters in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio.

In 1896, these six men, who together owned or controlled more than 500 theaters across the nation, joined forces to form what came to be known as the Theatrical Syndicate.

Suddenly

That August, they met for lunch at the newly constructed Holland House, a hotel on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. They were frustrated. They believed, not unreasonably, that the “making of routes for theatrical attractions in the United States was in a most disorganized and economically unsound condition.” Sometimes a touring company would arrive in a town only to find another theater offering the same play they had brought; sometimes they had to discontinue a successful run because another production had booked the theater. Worse still, as theater owners, they felt they were at the mercy of the actor-managers who had the power to force them to pay more for a production than they wanted to.

Something needed to change.

They decided, according to Daniel Frohman, Charles’s brother, who wrote an admiring account of the formation of the Syndicate in his biography Charles Frohman: Manager and Man, that the “only economic hope was in the centralization of booking interests… Within a few weeks they had organized all the theaters they controlled or represented into one national chain. It now became possible,” Daniel crowed, “for the manager of a traveling company to book a consecutive tour at the least possible expense. In a word, booking suddenly became standardized.” And centralized.

To put it in business terms, their solution was to create a nationwide monopoly. They had drawn up and signed a contract that would run for five years from its signing on August 31, 1896, and at the risk of testing your patience, allow me to quote from it extensively so you can get a sense of the scope and exactitude of their intentions:

CONTRACT

That during the continuance of this agreement all of the following named theatres and places of amusement, to wit.

- Columbia and Hooley’s Theatres, Chicago;

- Columbia and Montauk Theatres, Brooklyn;

- Museum, Boston;

- California and Baldwin Theatres, San Francisco;

- New Century Theatre, St. Louis;

- Tabor Grand Opera House, Denver;

- Walnut Street Theatre, Philadelphia;

- Coates’ Opera House, Kansas City;

- Euclid Avenue Opera House, Cleveland;

- Alvin Theatre, Pittsburgh;

- New Creighton Theatre, Omaha;

- Talma Theatre, Providence;

- New Southern and Grand Opera House, Columbus;

- Valentine Theatre; Toledo;

- Lyceum Theatre, Cleveland;

- and Davidson’s Theatre, Milwaukee,

all of which are controlled by the parties of the first part [i.e., Charles Frohman and Al Hayman] or in which they are in receipt of income for services rendered; also:

- the Broad Street Theatre, Chestnut Street Theatre, and Chestnut Street Opera House, Philadelphia;

- Academy of Music, Baltimore;

- Lyceum Theatre, Baltimore;

- Lafayette Square Opera House and Columbia Theatre, Washington. D.C.;

- and Park Theatre, Philadelphia,

all of which are controlled by the parties of the second part [i.e., Samuel F. Nixon and J. F. Zimmerman] or in which they are interested or from which they are in receipt of income for services rendered: and also

- the New Masonic Theatre, Nashville;

- Grand Opera House, Memphis;

- Staub’s Theatre, Knoxville;

- St. Charles Theatre and Academy of Music, New Orleans;

- Walnut Street Theatre, Philadelphia;

- Coates’ Opera House, Kansas City;

- Euclid Avenue Opera House, Cleveland;

- Alvin Theatre, Pittsburgh;

- New Southern and Grand Opera House, Columbus;

- Valentine Theatre, Toledo;

- Lyceum Theatre, Cleveland;

- and Davidsons Theatre, Milwaukee,

all of which are controlled by the parties of the third part [i.e., A. L. Erlanger and Marc Klaw] or in which they are interested or from which they are in receipt of income for services rendered: and all other theatres or places of amusement which may be hereafter (during the continuance of this agreement) acquired by either of the parties of the first, second, or third parts hereto, shall be booked with attractions in conjunction with each other; that is to say, no attraction shall be booked in any of the said theatres or places of amusement (or in any which may be hereafter acquired as aforesaid) which will insist on playing on opposition theatre or place of amusement in any of the cities above named. [emphasis added]

Those theaters mentioned above were not the only theaters they owned–oh no. They also owned many, many more theaters across the country in the small towns between the cities, which they also agreed to only book with Syndicate productions. And so according to the contract, if a touring production refused play in a single Syndicate-owned theater in any of the cities listed above, they were prohibited from performing in any Syndicate-owned theater including in the small towns where individual Syndicate members owned theaters. If a production wanted to perform in a Syndicate theater, they were locked in to the whole shebang.

The members agreed that they would combine all the net proceeds from the theaters listed above and split them evenly, but each were not required to include the proceeds from the smaller theaters they each owned or controlled. The success of the Syndicate, however, was based on their control of the small-town theaters. As theater historian Landis K. Magnuson writes in Circle Stock Theater: Touring American Small Towns, 1900-1960:

“The image of the “circuit” is misleading when called upon to describe the true strength and backbone of the Syndicate, however. Rather, the image of a passage through a narrow corridor is somewhat more helpful in reconstructing the Syndicate’s methods, because the Syndicate put to use its holdings in theater property in a way unlike any other management organization of the period. Although the Syndicate controlled the bulk of first-class theaters in the major metropolitan centers, the fact that it controlled the theaters in communities located between such theater centers provided its true source of power. Without access to these smaller towns, non-Syndicate companies simply could not afford the long jumps from one chief city to another. Thus, the Syndicate actually needed to own or manage only a small percentage of this nation’s theaters in order to effectively dominate the business of touring theatrical productions–to monopolize ‘the road.'”

Let me put this plainly: if you were the manager of a combination company, you were screwed.

If you wanted to keep control of your company and remain independent, and thus refused to sign with the Syndicate, you were reduced to playing in second-class theaters, lodge rooms, dance halls, even skating rinks. The famed French actress Sarah Bernhardt famously refused to sign with the Syndicate and instead toured the country performing in an enormous tent! On the other hand, if you did sign with the Syndicate, they frequently demanded a percentage of the combination company’s share as a “gratuity” for arranging a “good route.” This gratuity could be as much as 50% of the producer’s share!

The Theatrical Syndicate positioned themselves between the artists and the audience by owning the platform that each group used. Thus, they were both a monopoly and a monopsony.

Monopoly

The Syndicate’s monopolistic power derived from its control over theater bookings. By 1903, it controlled all but a few first-class theaters in major cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago, as well as numerous one-night stands across the country. This led to

• Control over Actor-Managers (which we would now call “producers”): The Syndicate’s extensive network of theaters allowed it to dictate terms to producers, effectively creating a sellers’ market for theatrical bookings. Producers who wanted to reach a large audience had to comply with the Syndicate’s demands, which often included giving the Syndicate partial ownership of their productions. Producers who refused faced boycotts, unfavorable routes, or complete exclusion from Syndicate theaters.

• Control over Playwrights: While the sources don’t explicitly mention the Syndicate’s direct control over playwrights, their control over producers indirectly impacted playwrights. The Syndicate’s focus on commercially successful plays pressured producers to choose plays that would appeal to a broad audience. This, in turn, may have influenced playwrights to write for mass appeal rather than artistic merit, as producers held the power to determine which plays were produced.

Monopsony

The Syndicate also acted as a **monopsonist **by controlling access to a vast network of theaters, which constituted the primary market for theatrical productions.

• Control over Theater Owners: The Syndicate’s exclusive booking contracts with numerous theaters effectively created a buyers' market for theatrical productions. Theater owners who signed with the Syndicate could not book productions from other sources, limiting their options and bargaining power.

• Control over Audiences: By controlling which productions played in which theaters, the Syndicate also exerted considerable influence over what audiences could see. This control limited audience choice and potentially stifled artistic innovation and diversity in theatrical offerings.

The Syndicate’s dual role as both a monopolist and a monopsonist solidified its control over the American theater industry for over a decade. This dominance allowed it to prioritize profits, leading to the commercialization of the theater and a decline in artistic experimentation. This system ultimately benefited the Syndicate members at the expense of playwrights, producers, theater owners, and audiences alike.

Coming next: Criticism of and Resistance to the Syndicate, and the Connection to Today’s Theater

Nicholas Carr on the Contemplative Gaze

As always, Alan Jacobs (@ayjay) calls our attention to extraordinary writing, not only his own but of others as well. In this case, it is Nicholas Carr writing about the act of contemplation, both of art and of nature. And while I will have to think more about his preference for what he calls “unenchantment,” this essay is worth reading if only for the lengthy Nathaniel Hawthorne quotation in which he describes sitting in Sleepy Hollow just…being aware.

Michael Rushton is doing an excellent job of dismantling all the ways we miss the boat when we’re trying to run an arts organization. This one is about why metrics don’t work: open.substack.com/pub/micha…

True Wealth

“With the broad acceptance of scarcity, the drawdown of resources ensues, and business begins: the race for the best education in a world believed to be short of good teachers; the race for the best-paying jobs in a world believed to be deprived of respectable work and access to resources; the competition to acquire land and housing in a world where we believe there is a housing shortage; the pressure to buy all the right advantages and implements for our children in a world that is believed to have limited space and opportunity for them; the hustle to work hard and bank and invest and save in a world where we believe money is the only means of having our needs met. The output of all this work is not more true wealth. It’s simply more money. And the bank of true wealth—love, resources, time, and deep engagement—gets depleted.”

Redefining Rich by Shannon Hayes